by Lisa Brewer | Our Coast Weekend | March 16, 2022

Amiran White has a message to share from the Chinook people. The photographer, who has spent many years documenting the five tribes together known as the Chinook Indian Nation, hopes to increase public awareness of the tribes’ decades long struggle for federal recognition.

The Clatsop, Wahkiakum, Kathlamet, Lower Chinook and Willapa tribes “have resided at the mouth of the Columbia River since time immemorial,” writes Tony A. (naschio) Johnson, chairman of the Chinook Indian Nation. Johnson’s words appear in a book of photographs and essays, also featuring White’s documentary work. These images showcase Chinook ancestral lands, canoes, garments and ceremonies, aiming to illuminate the tribes’ history, challenges and enduring cultural traditions. “I got involved about seven years ago when I first heard their story at the University of Oregon. Tony Johnson and some of his family were there and gave a talk,” White said. “It is quite remarkable, everybody continues to have this true resilience, just marching forward,” she added.

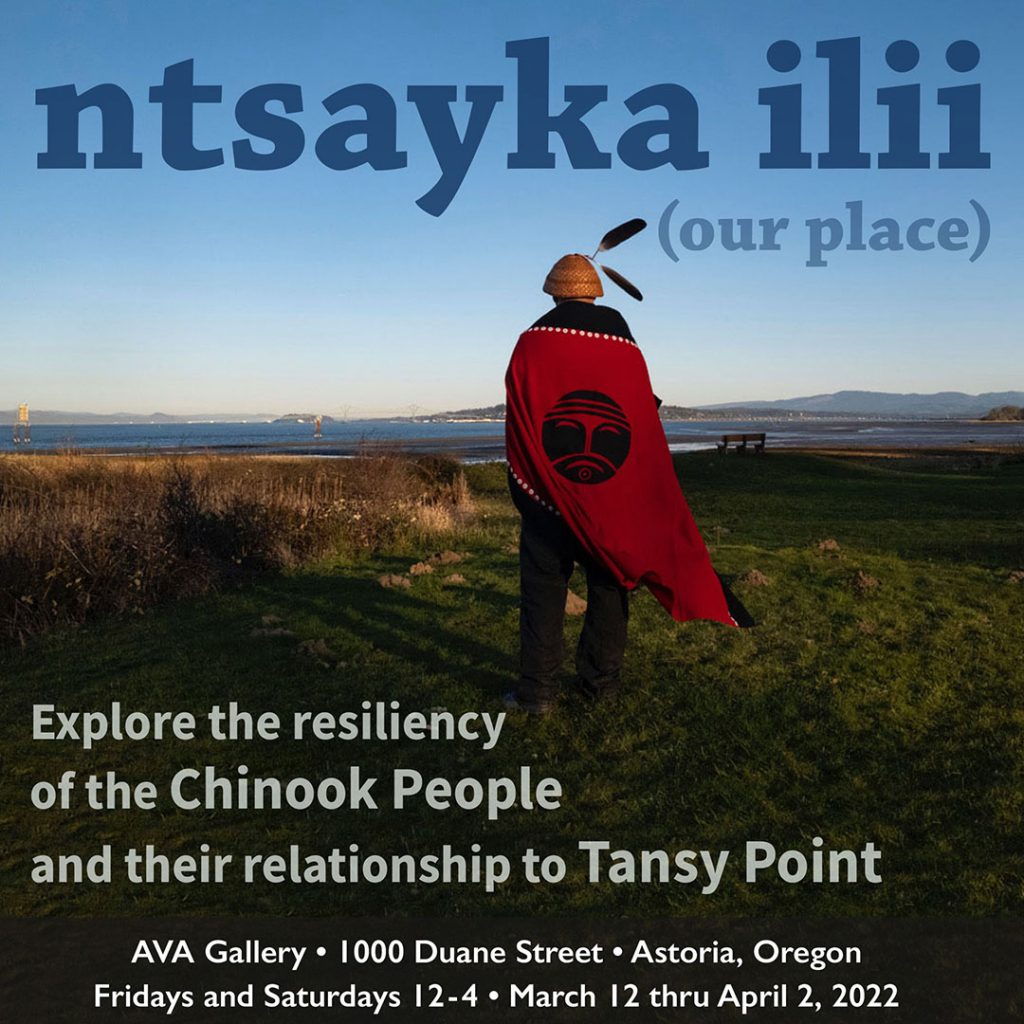

The photographer’s latest exhibit, in collaboration with a group of Chinook artists, explores that very resiliency, using past and present images, carvings, baskets and informational pieces. “ntsayka ilii: our place,” a title drawn from the Chinook Wawa language, is now on display at Astoria Visual Arts through April 3. The exhibit chronicles the tribes’ relationship to Tansy Point, where Chinook villages once stretched along the Columbia’s waterways.

“This exhibit is about the tribe’s acquisition of some land at Tansy Point, and their relationship to that land, why it’s so special to them. So there are some images from Tansy Point, images of daily life and other events that show who the modern Chinook are,” White said. Today, Tansy Point is a both a place of celebration and a reminder of past and present challenges.

In 2019, the Chinook Indian Nation acquired a heavily forested 10 acres alongside Tansy Creek near Hammond, the first property in Clatsop County to be owned by the nation. The site offers a chance to achieve significant cultural preservation. Soon, the nation hopes to restore the undeveloped land, revitalize the creek bed and eliminate invasive plant species. The restored property could then be used for cultural and environmental education programs for tribe members and the wider community.

The site is one of historic resistance. In 1851, Anson Dart, superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon Territory, camped at Tansy Point for four days. Assigned to secure the title to Chinook coastal lands, he set off to prepare the tribe for relocation to a reservation east of the Cascade mountains. Instead, each of the Chinook Indian Nation tribes negotiated treaties at Tansy Point, vowing to remain in the lands of their ancestors.

In the century and a half since, the Chinook people have continued to face trials, including subsequent negotiations, land claims and varying degrees of acknowledgment from local, state and federal officials. Through it all, the tribes have remained faithful to their identities, traditions and lands, as seen in Astoria Visual Arts’ latest exhibit.

Born and raised in the United Kingdom, White began her photojournalism career at the Associated Press in Portland. She then spent 10 years working as a staff photographer on various daily newspapers in Oregon, Pennsylvania and New Mexico before freelancing as an independent photographer. White has been the recipient of a variety of awards, including a Pulitzer Prize nomination and Golden Light Award. Most recently, she has been chosen by the Oregon Arts Commission as one of 10 awardees for the organization’s 2022 Individual Art Fellowship.

But White is reticent to take credit for this project. “It’s really about the Chinook,” White said. “I’m just the vessel. It’s about getting their voice heard. I hope that people are able to come, learn and ask questions,” she added.