Against all odds

The Duwamish tribe’s fight for recognition

Tacoma Weekly | November 23, 2021

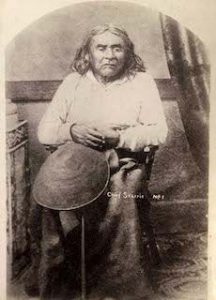

Seattle is named after Duwamish and Suquamish Chief Si’ahl.

Old Tom and Madeline lived in a house on Portage Bay across from today’s UW campus.

Chief Si’ahl’s daughter Kikisoblu (Princess Angeline).

Cecile Hansen, the great-great-niece of Chief Seattle, has been tribal chair since 1975.

In 2009, the tribe opened the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center and “Birthplace of Seattle” Log House Museum.

They gave up thousands of acres of land in a treaty agreement and got nothing in return. They are the first people of present-day Seattle, but they are still not a federally recognized tribe. They have been working to restore their federal recognition since 1978 but have hit roadblocks all the way including opposition from other Puget Sound tribes.

This is the Duwamish Tribe, and they have launched a renewed push to be recognized by the federal government. Bolstered by President Biden appointing Deb Haaland as the first Native American interior secretary, the person who oversees the office in charge of recognizing tribes, a group called Stand with the Duwamish to Restore Federal Recognition is leading the effort. A petition at Change.org has received more than 70,000 signatures toward its goal of 75,000.

More public support for the tribe is coming in the form of “rent” payments. Real Rent Duwamish is a grassroots movement to give donations to the tribe as restitution and recognition for these original inhabitants of the land. For the tribe, the program is a valuable tool to educate more people about the Duwamish and their battle for federal recognition. More than 4,500 people contribute to Real Rent Duwamish, totaling around $20,000 a month for the tribe.

The Duwamish were the first signatories on the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855, which was signed by other tribes including the Suquamish, Lummi, Skagit and Swinomish. The treaty guaranteed hunting and fishing rights and reservations to these tribes which, in return, gave up their land as part of the agreement. The Duwamish lost more than 54,000 acres of their homeland to the U.S. Government, lands that today encompass Seattle, Renton, Tukwila, Bellevue, Mercer Island and much of King County. However, the government reneged on its promises to the Duwamish and to this day, none of them have been kept.

As the Duwamish’s territory became settled by more and more European-Americans arriving in Puget Sound, Duwamish tribal members had to leave their ancestral villages and take shelter on the designated reservations of other nearby tribes. This was the only way that the Duwamish could hope to preserve their heritage and culture, and why so many with Duwamish ancestry became part of the Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Tulalip, Suquamish, and Lummi tribes, all of which were granted reservations through the Treaty of Point Elliott. To make matters worse, especially for the Duwamish, in 1865 the Seattle Board of Trustees passed a law banning Native Americans from living in Seattle and the following year, non-native residents blocked a proposal for a Duwamish reservation.

Over the ensuing years, the Duwamish tribe continued and maintained their communal ties, and the federal government interacted with and acknowledged its relationship with the tribe on numerous occasions. In 1978, the tribe started the extensive, and costly, process for federal recognition by filing their first petition with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The tribe received a major setback two years later when U.S. District Judge George Boldt declared that the tribe had not existed continually as an organized tribe, required under federal law, and was therefore ineligible for treaty fishing rights.

Boldt made this decision because of a 10-year gap in the Duwamish tribal record from 1915-1925, which also led the Bureau of Indian Affairs to deny recognition in 1996. Due to Duwamish tribal members diligently gathering evidence of their continuity through news reports, oral histories and bloodlines, the BIA reversed its decision – but it was short-lived. The tribe received acknowledgement on Jan. 19, 2001, by the Clinton administration, but it was reversed shortly after President George W. Bush was inaugurated and suspended many of Clinton’s orders he signed just as his presidency ended, including federal recognition of the Duwamish.

In 2015, the U.S. Department of the Interior issued its final decision that the Duwamish are not entitled to acknowledgment as an Indian tribe. The tribe, now totaling about 600 members, has appealed and the case is still pending in the Interior Board of Indian Appeals.

WHY THE OPPOSITION?

The Muckleshoot, Tulalip, and Puyallup tribes oppose granting federal recognition to the Duwamish tribe. The Tacoma Weekly reached out to Muckleshoot Tribal Chairman Jaison Elkins for more information on the opposition, and he referred us to the website TheRealDuwamish.org, where numerous reasons are cited.

As stated on this website, “Today, the vast majority of Duwamish descendants are members of the Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Tulalip, Suquamish, and Lummi Tribes. But a small group calling itself the Duwamish Tribal Organization is deceptively using the name of our ancestors in an effort to appropriate our history and our culture. (The Duwamish) is not an Indian Tribe, but rather a small group descending from a handful of early marriages with non-Indian settlers who chose to assimilate rather than move to the reservations established for the Duwamish people.

“They are not an Indian Tribe, and support for their effort is an affront to our sovereignty and the culture we have fought so long to preserve.”

According to the opposing tribes, the U.S. government established the Muckleshoot and Port Madison reservations as homelands for the Duwamish people. “The Duwamish group is not a successor to the historic Duwamish tribe that signed the Treaty of Port Elliott. In July 2015…the Obama Administration…concluded the group is not a continuation of the historic Duwamish tribe and has never constituted the social community or exercised political authority over its members necessary for federal recognition.”

It stands to reason that there are economic issues contributing to the opposition as well. If the Duwamish were to be federally recognized and granted their own reservation, they would be entitled to have a casino hotel enterprise and downtown Seattle would be the optimum site choice.

A showplace casino on the Seattle waterfront would attract a robust clientele of business travelers, tourists, and people from affluent parts of Seattle and surrounding areas all going to enjoy a more conveniently located casino experience. This would make for more competition for the Puyallup tribe’s Emerald Queen Casino, the Tulalip Resort Casino and the Muckleshoot Casino Resort. It could also bring further competition to our state’s newly legalized sports betting, which is available exclusively at nine select tribes including the Puyallup, Muckleshoot and Tulalip tribes.

THE DUWAMISH TODAY

Despite no federal recognition, the Duwamish remain united as significant contributors to the wellbeing of their own people and the broader population. As the host tribe for Seattle and King County, the tribe holds an important position in representing our region’s indigenous peoples. They provide speakers for public engagements in communities, schools, universities, and heritage and service organizations. The Duwamish routinely greet visiting foreign and tribal leaders, and tribal board members sit on boards of key community and governmental organizations concerning environmental, heritage, tourism, and neighborhood issues.

The tribe is governed by a 1925 constitution and bylaws. Since 1975, Chief Seattle’s great-great-grandniece Cecile Hansen has been the elected chair of the Duwamish tribe’s six-member tribal council. There have been fewer than six changes in Duwamish leadership in the last 85 years. Hansen is also a founder and former president of Duwamish Tribal Services, which works to promote the social, cultural, political and economic survival of the Duwamish Tribe, to revitalize Duwamish culture, and to share its history and culture with all peoples.

In 2009, the tribe opened the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center on purchased land near their ancient settlement at the mouth of the Duwamish River. Tribal gatherings are held there at least once a year, and the center is available for rent for events like wedding receptions, business meetings and trade shows.

The Duwamish Upland Reforestation Project is the tribe’s ongoing effort to protect, restore and reforest 5,800 square feet on the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center property to sustain native food and medicine, resource producing vegetation, and wildlife habitat in relation to Duwamish culture. Tribal member James Rasmussen is a founding member and Superfund manager of the Duwamish River Community Coalition that addresses ongoing pollution and cleanup plans for Seattle’s lower Duwamish River, a 5.5-mile-long Superfund site.

The Duwamish people continue to be recognized by the BIA as legal Native Americans, but not corporately as a tribe. They have had to stand up for themselves not only in front of the U.S. government, but their own fellow Native Americans as well. How they have been treated is a stain on our region’s history and character – wrongs that need to be righted to bring honor back to the very city that bears the name taken from the Duwamish’s esteemed leader Chief Si’ahl.